FATHER'S DAY, A DAY LATE

"Close your eyes Have no fear The monster's gone He's on the run and your daddy's here" - John Lennon

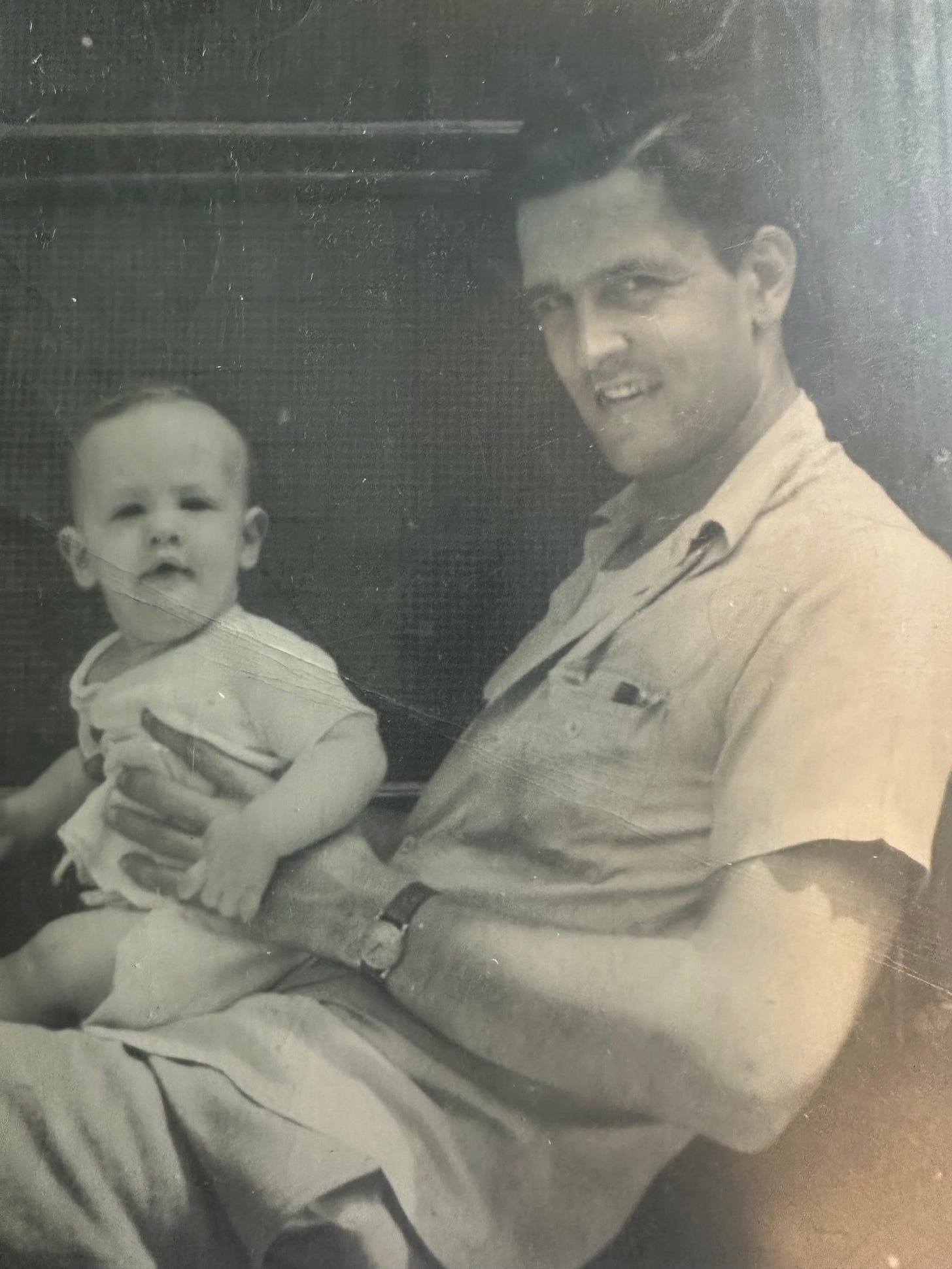

My father was an engineer. A bridge and highway man at first, with a bow tie, a short sleeved button down white shirt, close cropped hair, and a drafting table in the center of a room filled with drafting tables. Then they asked him to learn about tunnels and he did. He also learned about how to run a business because they asked him to open an office for his company in New York City. The drafting table moved to the corner of a room with a view. The company was going to be doing the engineering on what National Geographic Magazine would call “the eighth engineering wonder of the world.” We moved to New Jersey. He took a course from Harvard to learn the business-running part. He studied on his own and asked people who knew what they were talking about in order to learn about tunnels and how to build them. At one point two different newspapers referred to him as “the world’s foremost expert on tunnels.” I always thought and said out loud that that phrase is something that Freud would have loved to pontificate over.

He and I did not see eye to eye on very much after I chose to work as an actor rather than as an engineer. Being an engineer had been my plan but that was primarily because it was the best way to have a relationship with my father. By the time I was old enough to talk seriously with him about the ways of the world he was so deeply into learning about tunnels and businesses that he didn’t have a lot of time for serious talks with someone who would quite possibly have disagreed with him. He was an old school Republican who thought Nixon had been railroaded out of office.

When I was young he was an idol, a god, the only image of a man that I had to look up to, to aspire to becoming. After I had been out in the world a bit, moved around and began to find my own sense of how things worked he was not so impressive. I never perceived him as weak, or corrupt, or dishonest. He was just wrong headed, deluded by the zeitgeist that he had experienced. I, of course, being young, was not deluded by my own zeitgeist.

After I had been working in the theatre for about ten years I was asked to play the son, Chris, in a production of Arthur Miller’s play, All My Sons, to be directed by a friend, Timothy Near. I had some time to prepare and I went to visit my parents in North Carolina to get some quiet while I studied the script. I asked my father to read the play and to talk with me about it. In case you don’t know it the play was written in 1946 in the aftermath of World War II. The father in the play, Joe Keller, is the sole owner of a tool and die shop in Ohio. During the war he and his partner converted the shop to make airplane parts for the war effort. I thought that my father, having lived through the war, having seen action in the South Pacific on aircraft carriers, and having known men in the business world could give me some insight into the world I was going to be stepping into and living in for the next three months or so.

In the play it is revealed that at one point during the war, working hard to meet the demand for equipment, Joe Keller, my father in the play, had authorized a shipment of parts that he knew to be defective and potentially dangerous if used in planes. He had shifted the blame for the decision to his partner, a business man and not an engineer. When planes crashed and twenty-one men died his partner went to prison and Joe was found innocent and thrived in his business after the war. My older brother in the play, the golden boy of the family, had been a pilot in the Pacific and had died when his plane went down. It was never known and never discussed whether he had died because of one of the faulty parts. My character, Chris, idolized his father and was home on the particular weekend of the play to announce his engagement to the girl next door, the daughter of Joe’s partner, the man who had recently died in prison. It is a wonderful play about family, about duty, about honesty, and about fathers and sons and the complicated relationships that can grow out of that union.

My father was retired by this time so he read the play quickly and the next day we sat in the big family room, he in his chair near the television, next to the wall of windows that opened into the ivy covered backyard, me in my customary chair by the kitchen door at the table where we took our meals. I don’t remember the whole of the conversation except that I probably asked him a lot of general questions about what the world was like just after the war. He was a man from the Midwest, had a brother who lived in Cleveland where the play takes place. The depression and then the war had been his own personal history but he was always a man who was able to stand back a bit and see the world in an historical context and not just from his own point of view. So he offered a good point of reference for me as I tried to get deeper into the play. I learned a bit about his experience during the war working on an aircraft carrier that ferried damaged planes back and forth from San Diego to islands in the Pacific. He had never talked much about the war and even now did not go into any personal recollections but as we got deeper into the play he began to speak in a softer, less objective tone of voice. He said that though he liked the play and hoped I would be a big success in it he didn’t believe such a thing could ever actually happen. He did not believe that a man, a seemingly good man, as Joe Keller was, a good, loving father, a man who had built a successful business, had a solid marriage, a man who was considered a pillar of the community, could ever do such a horrible thing, could ever betray, not just his partner and friend, but his country and the men fighting to defend it. As he spoke his eyes watered and his voice got weaker with an uncharacteristic tremor. Men of his generation were not as emotionally fluid as perhaps men are becoming today. And men who had experienced the depression followed immediately by war, at whatever distance, learned that emotion does not necessarily increase functionality when stress is high and one needs to perform. So I understood his effort to restrain his feelings and I also understood the depth of the emotion over which he was trying to maintain control. I had never seen my father as shaken as he was discussing another man’s betrayal. I am sure that discussing the war gave him access to feelings that he may not have acknowledged in all the time since his return to civilian life. But the key to me at the time and to this day was his own integrity, his morality, his sense of what is right and what is wrong and the importance to him that a man protect that integrity, hone that morality, and stand for what he sees as right and what is wrong. Simply do the right thing.

My father left me a lot when he passed twenty three years ago. A sweater and a shirt that I still wear. Some tools of the engineering trade passed down from his father and now to me. A double barreled twenty-gauge shotgun that he hunted quail with when he was a boy and that I have fired one time only. A sense of tradition, of the value of family, and a very real and tangible idea of how important knowing what the right thing actually is and how difficult it is sometimes to come to and to stand by that belief. For that I am forever grateful.