I recently saw a play, the American premier, or so they said, of The Maltese Falcon. I had planned to write a review of it and I will. However, I got sidetracked into the author of the original text, the aforesaid Dashiell Hammett, his book, and the movie made from the book. So I decided to write about each of those entities and build toward a proper appraisal of the play. This is part one …

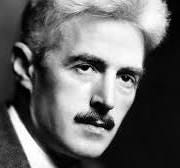

DASHIELL HAMMETT – THE MAN

In the 1970’s, in New York City, in one bar or another, places where actors and theatre people, working people, gathered after rehearsals and performances, or between gigs out of town, or just when there was nothing else to do, we would get together and talk, and drink. Since we were in a bar it seemed only logical to drink. Back then bars were places where people talked, argued, fought sometimes, and discussed their work and other people’s work and creativity in general. Social clubs or churches for artists. A bunch of theatre people talking is often like jazz. A lot is going on at once, and it can seem kind of cacophonous with many themes bouncing around and no central focus and then someone would take a solo, a rant if you will, spinning off of one melody into another, a leitmotif, kicking it around for a while, ultimately drawing everything back together, then off it would go again. I would occasionally riff on the best American novelist that ever lived: Dashiell Hammett. It was a riff that was intentionally provocative. It was from the heart, but I knew I was swimming upstream.

Not Twain. Not Hawthorne. Not Hemingway. Not Fitzgerald. Not Faulkner. Not Salinger. Not Bellow. Though an argument could certainly be made for any of those folks and others and was. If I wasn’t trying so hard to be provocative, I could have made that argument myself, but pumping up the name of a crime story writer, a pulp fiction writer, a guy whose books had been made into movies, and successful movies at that, a guy who wrote maybe five books and a bunch of stories in a magazine and then just seemed to stop writing, maybe because it got in the way of his drinking, was sure to get the blood and the conversation going by poking a hole in the balloon of pomposity that often exists amongst well-read, pseudo-intellectual, argumentative drunkards such as myself and others gathered around the table.

Hammett was born on a farm in Maryland and grew to an uncertain age in Baltimore where the water must be good for growing writers. He went to war in the Great War, got sick, never completely healed; worked as a Pinkerton agent for a number of years, was a detective, a spy, a strikebreaker; he was a man who worked both sides of the law as long as it paid. The Pinkertons made their own law, dependent only upon the needs of their employers, and they enforced it. He worked for a while out of Spokane. He left that work after being undercover in Butte, Montana, snooping for the copper kings in the early part of the 20th century when the battle between the very rich and the working class got especially ugly, violently brutal, and fatal for too many. Butte was where the labor movement in this country finally got fully to its feet, shouted its name and made a stand. Something about working on Maggie’s farm, working for the man, upset his stomach so he quit and turned his hand to writing and moved to San Francisco.

He wrote about what he knew. He wrote about himself, rather he turned himself and his experience into stories. He didn’t make stuff up, he wrote the truth that he had experienced, only he called it fiction and he gave people funny names. He didn’t adopt the posture of a writer, he worked as a writer. He sold stories about a crime fighter called the ‘Continental Op’ to the Black Mask and other pulp fiction mags of the day. His first novel, Red Harvest, grew out of his experience in Butte. He’d been asked by his bosses to murder the leading light of the International Workers of the World. He refused the offer and quit the Pinkertons. Andre Gide called Red Harvest “the last word in atrocity, cynicism, and horror.” It is on several lists of best American novels. There is a lot of blood, a lot of murder. A lot of betrayal. Hope for a better life is a fly on the wing in a small room trying not to get spattered with the gore. The experience turned him into an activist. He may or may not have joined the Communist Party but he was certainly a sympathizer. He went to prison for refusing to name names in front of some congressional committee. His companion of thirty years said he didn’t talk because he thought a man ought to keep his word. It was that simple. Like ‘Sam Spade’, the detective and main character in The Maltese Falcon says, in trying to explain to his lover why he is sending her over for the murder of his partner, whom he admits he didn’t even like, “When something happens to a man’s partner, he ought to do something about it.” It is that simple.

The gist of my riff on his greatness had to do with how quintessentially American he was as a man and as a writer. He wrote about crime and criminals and the United States of America is a crime. From the eradication of the culture, the language, the civilizations, and the population that lived here when we got here, to the enslavement of a kidnapped population in order to build an economy and thus an independent nation, to the systemic confinement of one half of our population for the first one hundred and forty four years of the democracy’s existence and the grudging respect we give to women even today, the government of these occasionally united states and its emissaries have committed crime after crime after crime against humanity, crushing and then ignoring anything that might be considered a moral sensibility. And the magnificent hypocrisy, which Hammett saw and loved for the drama it created, is that we crow from the rooftops of the world that we are the beacon of hope, of justice, of civilization for all peoples everywhere. The only hope that Hammett enjoys is in the thrill of language, of characters struggling to find their way in the dried blood darkness that admits very little light, and in the respect he has for the ingenuity of the liar, the con man, the criminal, even as he damns them. He loves them the way you love the artist in the circus on the high wire who will most excite you when they fall.

So you can see how my argument was a losing argument. How it flew in the face of the accepted wisdom of even the political left back in the day. The argument was meant to stand alone in the middle of the mayhem, as the man Hammett had, as the Continental Op, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, Lew Archer, as all the hard-boiled tough-as-their-hardworking-shoe-leather detectives that followed in his footsteps were. Hammett saw life on the other side with the gin clear vision of a man who lived there. But he walked among us, proudly alone, aggressively independent, uniquely American and always honest.